Tonya deCroce is currently traveling the globe in an effort to bring back to life the works and the stories of her grandfather –

Denver portrait photographer Edward Angelo deCroce.

She met with the curators of the Photography International Hall of Fame in St. Louis Mo. last week. She meets with Hassleblad in Gothenburg Sweden today and she’ll travel to Italian photographer Marcello Nitti next week.

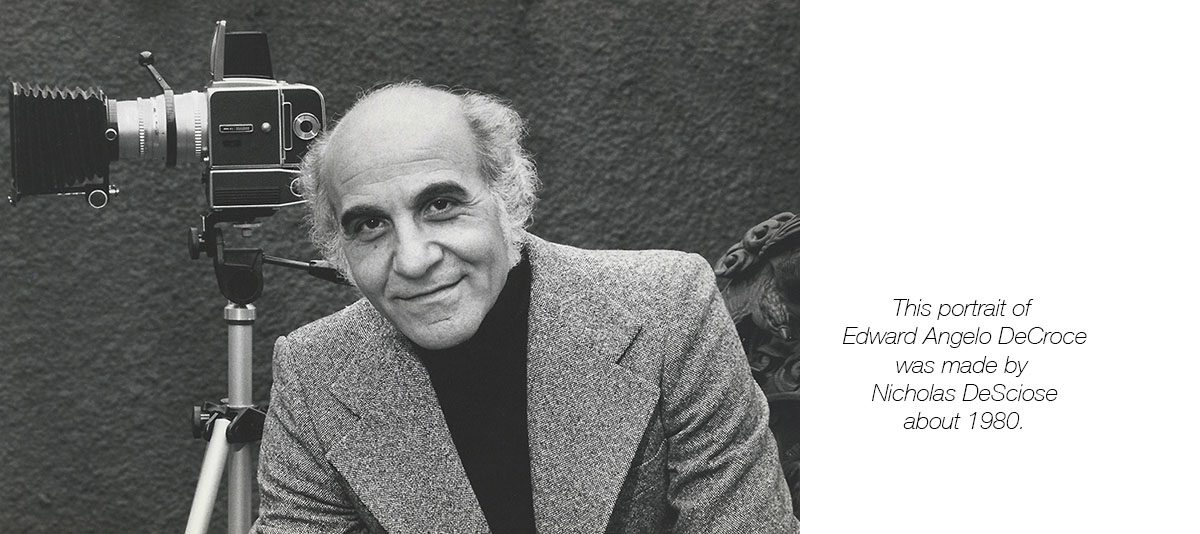

Locally she’s talked with iconic photographers such as Nicholas DeSciose and Denver photo-lab pioneer Bob Reed.

If anyone would like to share some stories with Tonya, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Today, she shared a letter received from the founder of Brooks Institute.

Your Magnificent Grandfather

Dear Tonya, I was delighted and excited when I had met Edward Angelo DeCroce on the Brooks Institute campus in that summer of 1980. When the West Coast School of Professional Photographers conducted seminars, we had so much to share in our lives.

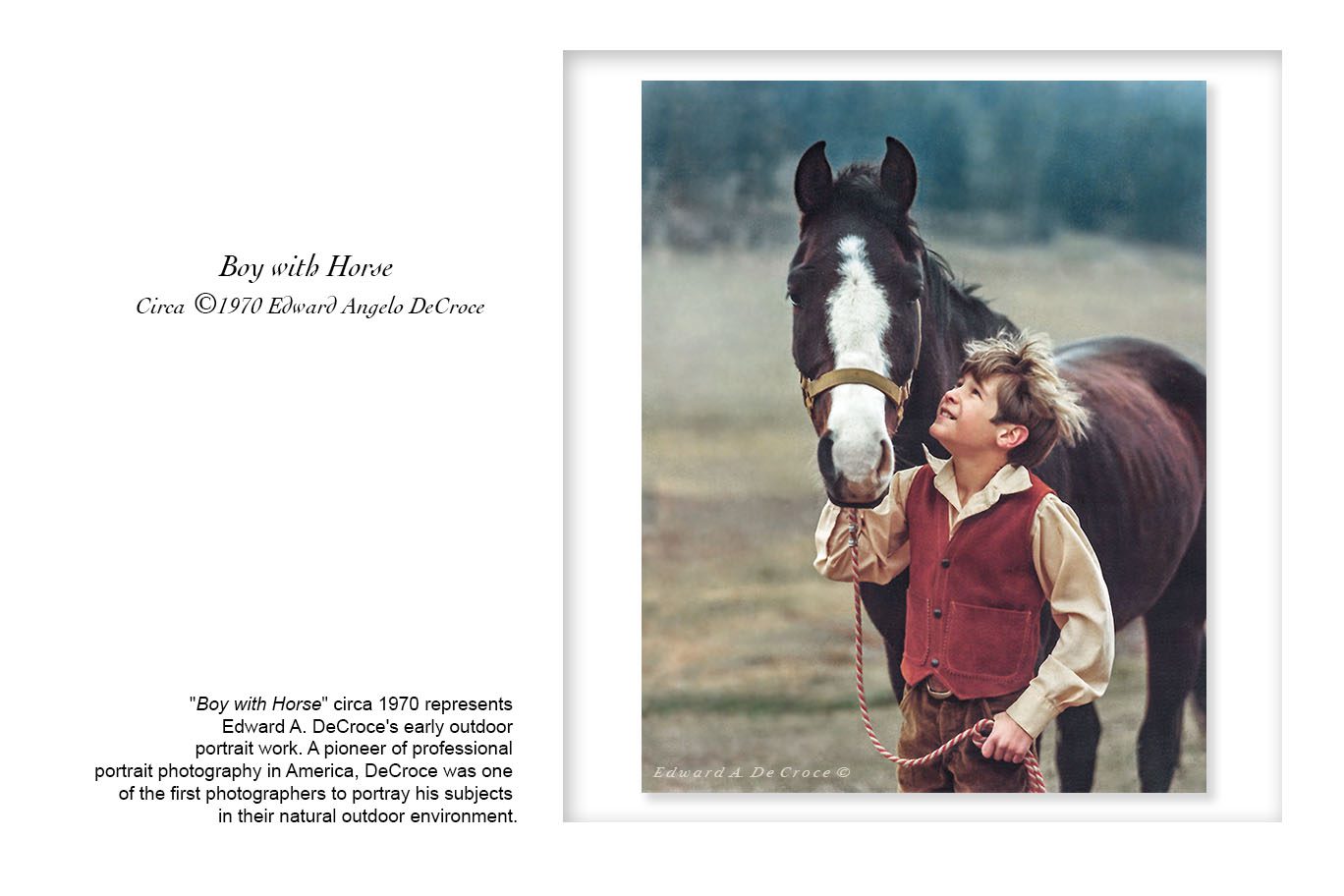

First was the use of the early Hasselblad camera system..we both shared Victor Hasselblad’s vision of the 70mm format for the highest quality. Edward chose the “out-of-doors with natural light to build his studio and in doing so enthralled so many photographers to switch to his natural lighting and incredible use of the natural environment. I chose to do the same in my underwater World with the camera that Victor himself presented me in 1961.

The style of outdoor photography that Edward Angelo Decroce presented …won the hearts of the entire photographic profession.

My best wishes on your journey Tonya.

………..with Love, Ernie Brooks

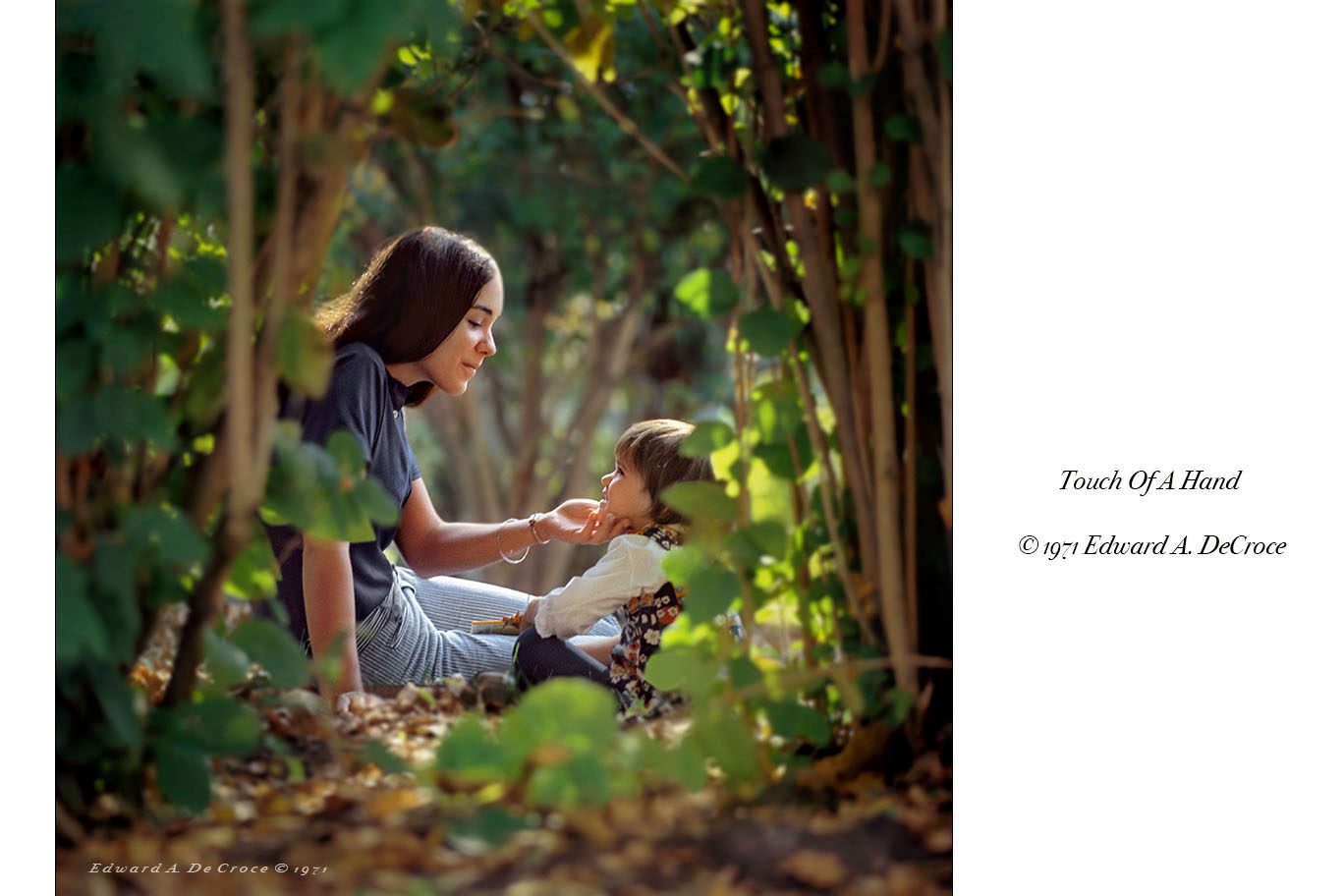

Touch Of A Hand ©1971 Edward Angelo DeCroce – was a hugely successful outdoor portrait for its time. A large 30″x30″ framed print was hung at the opening of the Epcot Center in Florida in 1982. Portrayed in “Touch Of A Hand are Edward’s daughter Olivia and granddaughter Tonya.

.

Archiving Past Works

The Work of Denver portrait photographer Edward Angelo deCroce

Denver portrait photographer Edward Angelo DeCroce dreamed big.

Shaped by the desperation of pre-WWII America, his life (1919-1983) was a quest to succeed. The hard times of his teen years forged in him a sprit that would ultimately precipitate his unique contribution to the world of photography.

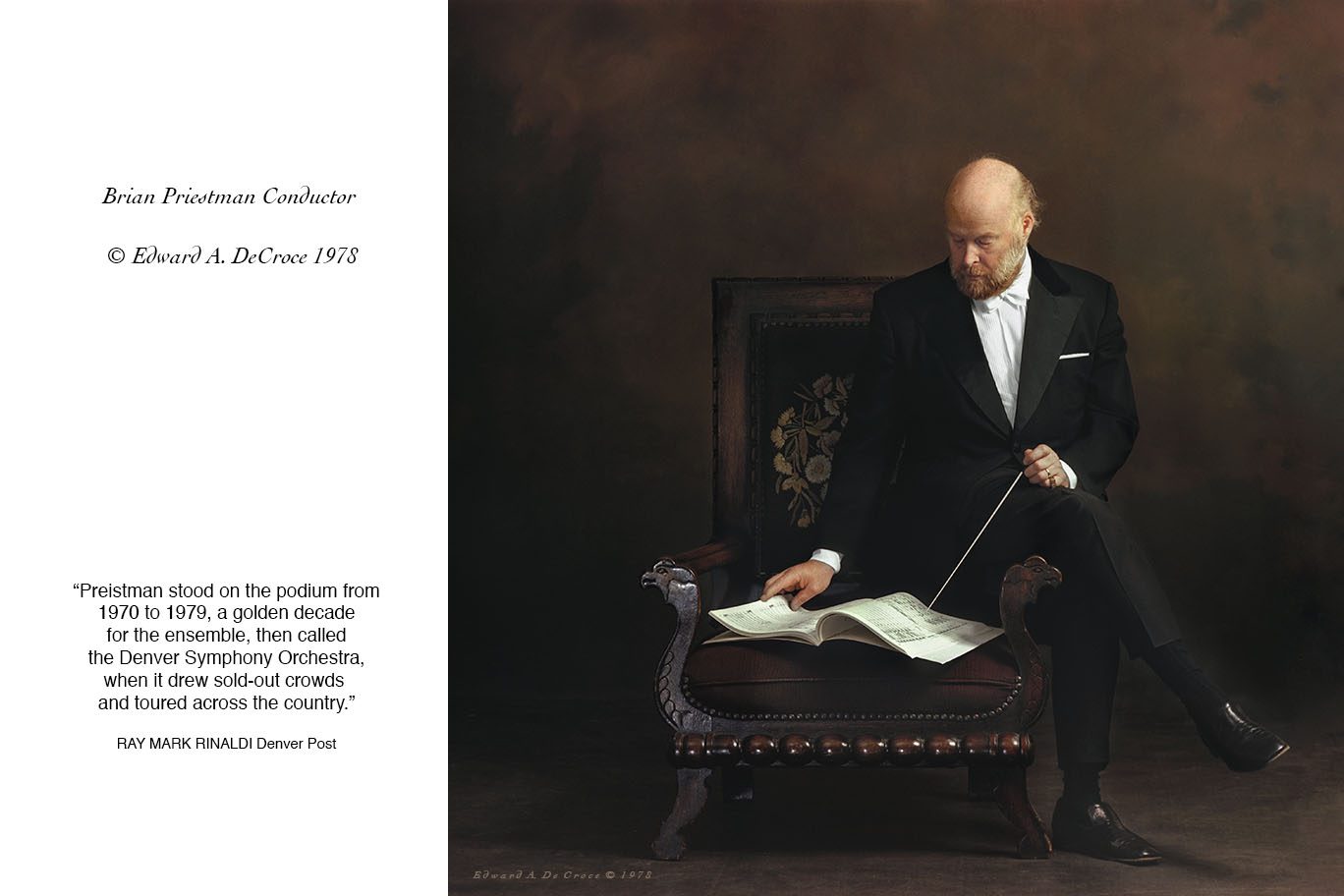

What makes the acclaim of DeCroce most remarkable is that his reputation was built not by creating glamour images of Hollywood stars, but by making portraits of ordinary people. Aside from a few accomplished symphony conductors, deCroce’s subjects were not famous. And his Denver photography studio was located in a part of town more known for the oldest profession than the heartfelt portrait photography that would define his life.

To judge art of the past through the eyes of the present can be a misleading endeavor. Tours of the Sistine Chapel, for example, begin by displaying artists’ work before 1500. So when viewers are finally shown the work of Michelangelo, they are in awe. They can grasp the concept that Michelangelo’s work was a giant leap.

Photography of the 20th century saw remarkable advancements in technology every decade. And innovative photographers reflected the changing times with new styles and ideas. In this way, Edward Angelo DeCroce was a true pioneer of professional photography. His work reflected society and influenced professional photographers around the world.

.

.

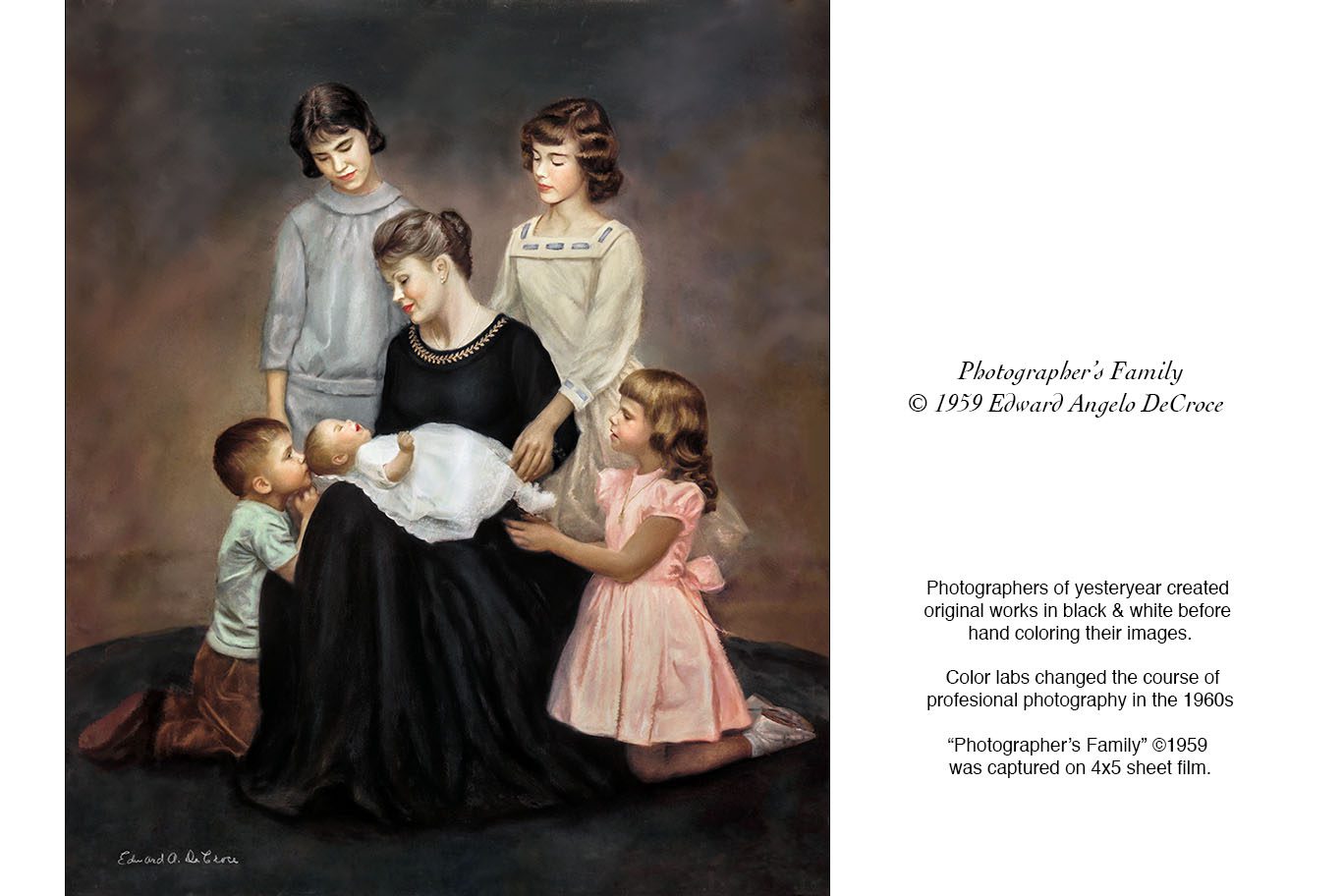

Early Innovation – Color & The Slim Line

As the Beat Generation morphed into the pre-hippie era of the early 1960s, DeCroce offered a style of portraits that fit the time. Always shot on white seamless, the slim-line portrait was made for baby boomers who donned ski clothes, penny loafers or capris. These portraits were made into unusually narrow vertical or horizontal prints – hence the name “slim-line”.

Color photography had existed for decades but mostly as an anomaly. For professional photographers, color remained on the horizon until the 60s. And even then, the sole color lab in the city (Bri Tone) catered to the amateur market. DeCroce dove deep into color photography creating his own lab in the basement of his studio. At first with “basket” technology, DeCroce Studio offered its customers color portraits years before they became the standard. When Dunning Photo came out with the Kreonite processor, deCroce invested in the giant 32″ version. The studio’s color printer, Carol Small, devoted herself to becoming an unparalleled expert. And by the mid 70s she had acquired a steady national clientele of pro photographers.

.

The Renaissance Portrait

Edward Angelo DeCroce continually strived for new techniques that would free him from the cliche. Influenced by Dutch painters like Vermeer and Rembrandt, DeCroce often photographed with just one light. He utilized very slow shutter speeds to capture ambient light and bounced a small light off ceiling or walls to augment ambient fill light. Studio lighting by deCroce was elegant in its simplicity. And to complete the aura of a photographic painting, DeCroce used oil paints on top photographs. Works were then finished with brush strokes of clear lacquer. With his color lab and finishing techniques, the studio offered large format prints in ornate frames not unlike museum portraits. He called these works The Renaissance.

Outdoor Portraiture & The Hasselblad – f4 @ 1/60

Simultaneously, DeCroce yearned to create works that reflected turbulent changes in American society. Working outside to capture a photojournalistic style of portraiture was not happening with the 4×5 format. And 35mm format was not substantial enough to create wall portraits with regularity. So in the 1960s deCroce traded one of his 4×5 cameras with a high school boy named Robert Penny in return for a Hasselblad 1000F. With the 70mm (2 1/4″ x 2 1/4″) Hasselblad, deCroce was free to create unique sets of portraits under (as he said) “God’s light”. Edward refused the notion of bringing his studio outdoors. He opted instead to work very simply without strobes or reflectors.

In photography, we adjust our exposures for any given light condition. But DeCroce reversed that formula. He sought light that would fit his exposure. The constants were always the same: 150mm lens wide open @f4, film speed @100 ASA (now referred to as ISO). For photographers steeped in the digital age, f4 is roughly equivalent to f2.0 on 35mm. With the two variables taken out of the equation, only shutter speed remained to control exposure. The use of monopods or tripods was often necessary.

DeCroce minimized the mechanics of photography for one simple reason. The Denver portrait photographer’s goal was to make a connection with the people in his images. DeCroce felt that continual tinkering with cameras and lights interrupts the flow and the mood of a portrait session. “A superficial interest in people results in superficial pictures.” He wrote.

.

.

.

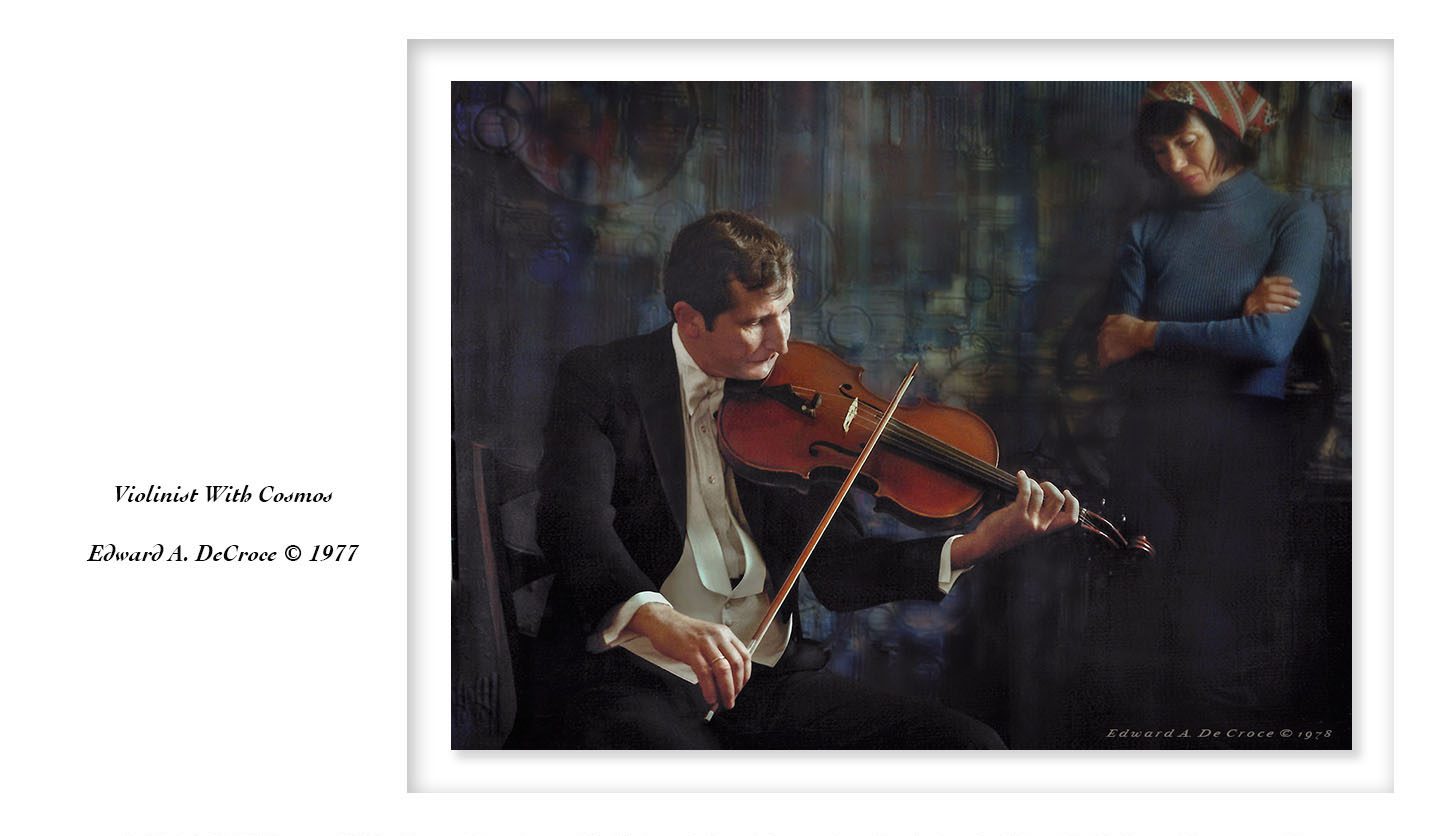

In Violinist With Cosmos 1977, Denver Symphony violinist Lee Yeignst plays during photo-session of portraiture by Edward A. DeCroce. As the Denver portrait photographer delved into his “self assignment” for the DSO, he surmised that his images became more vibrant when the musicians played their instruments.The addition of listeners added yet another element of design and realism to his works. The composition was created in the home of DeCroce’s longtime friend and internationally recognized painter Pawel Kontney. The giant painting entitled “Cosmos” hung in the entry room to Kontney’s home becoming the background of this composition. Pawel’s wife Imgard Kontney is the listener.

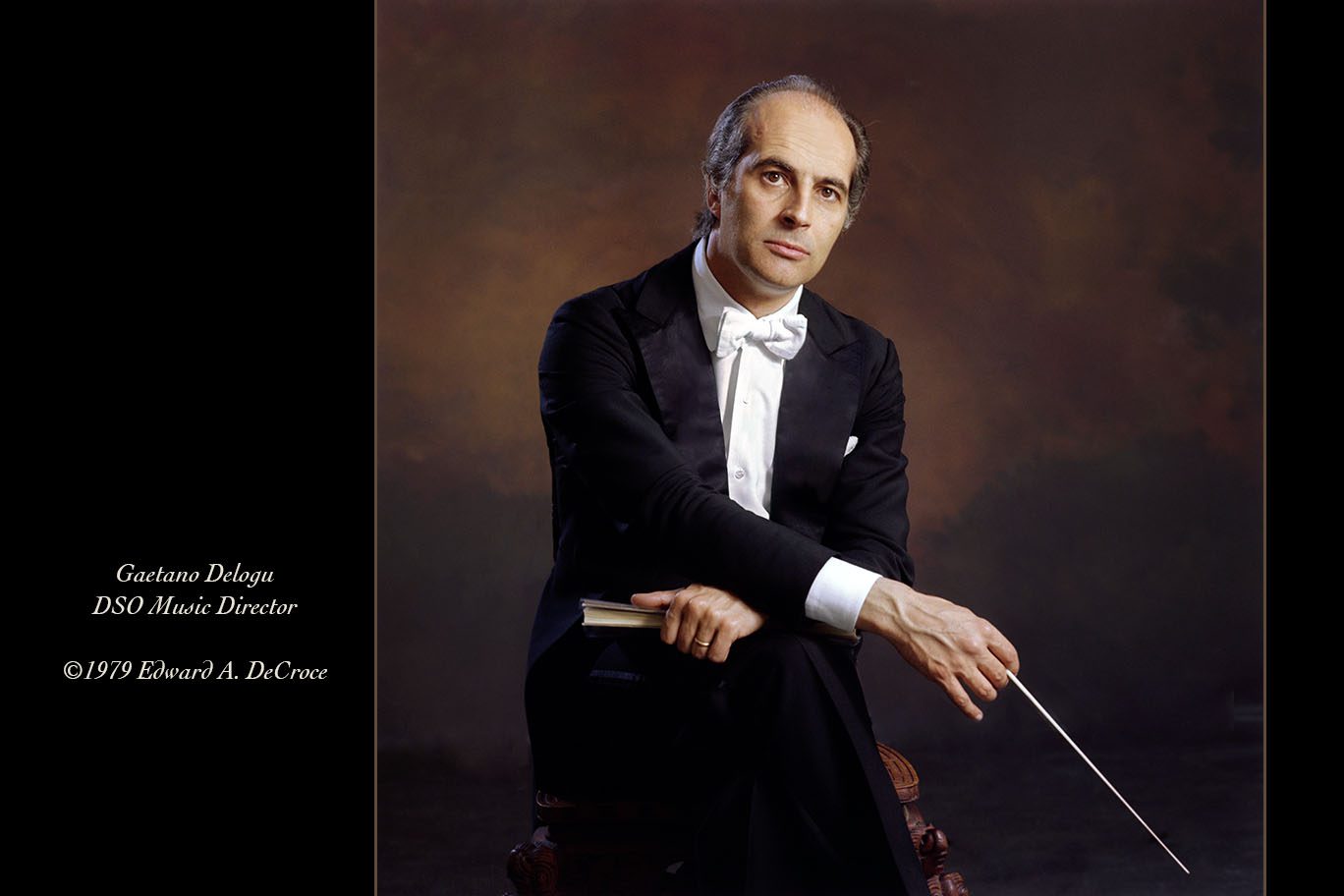

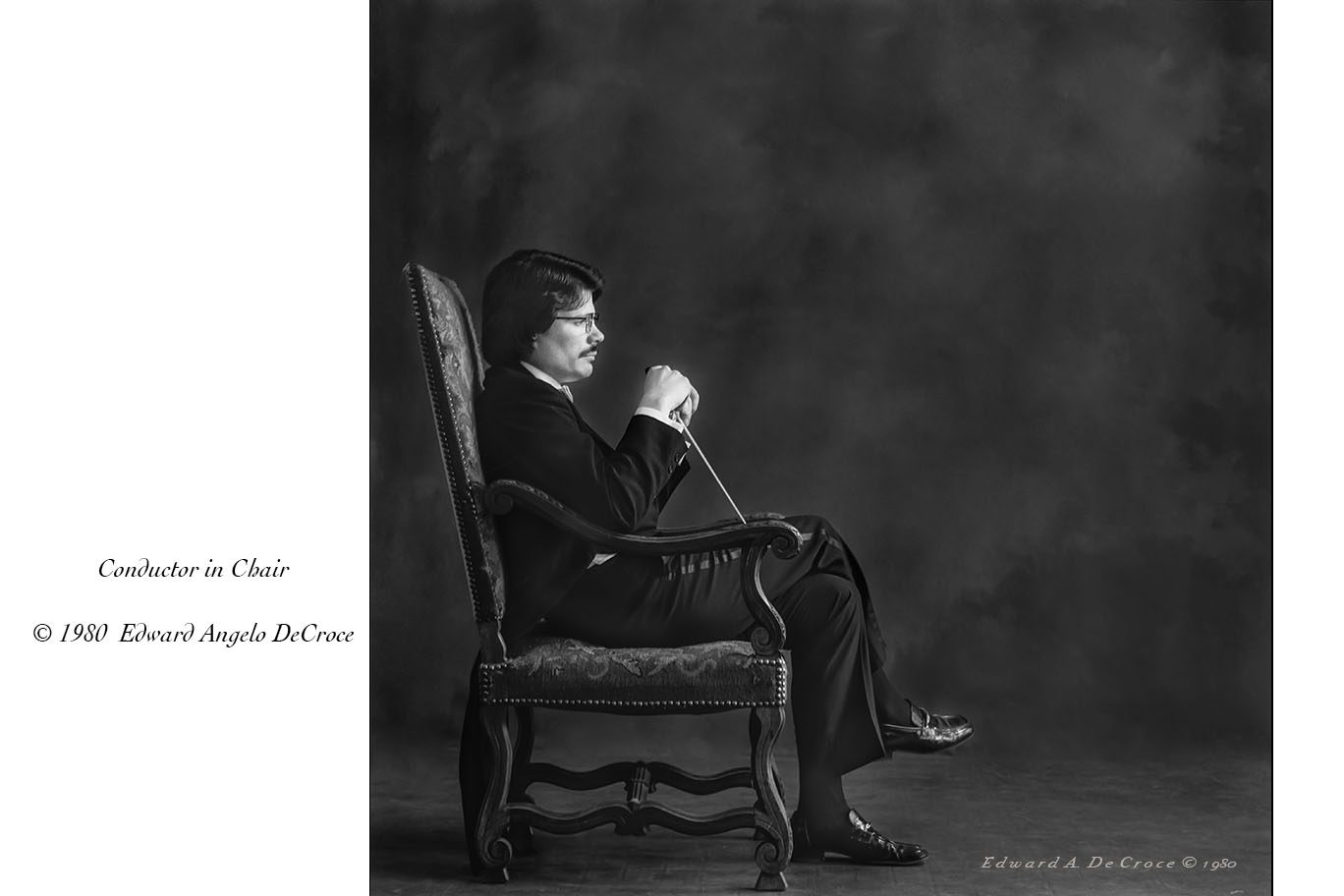

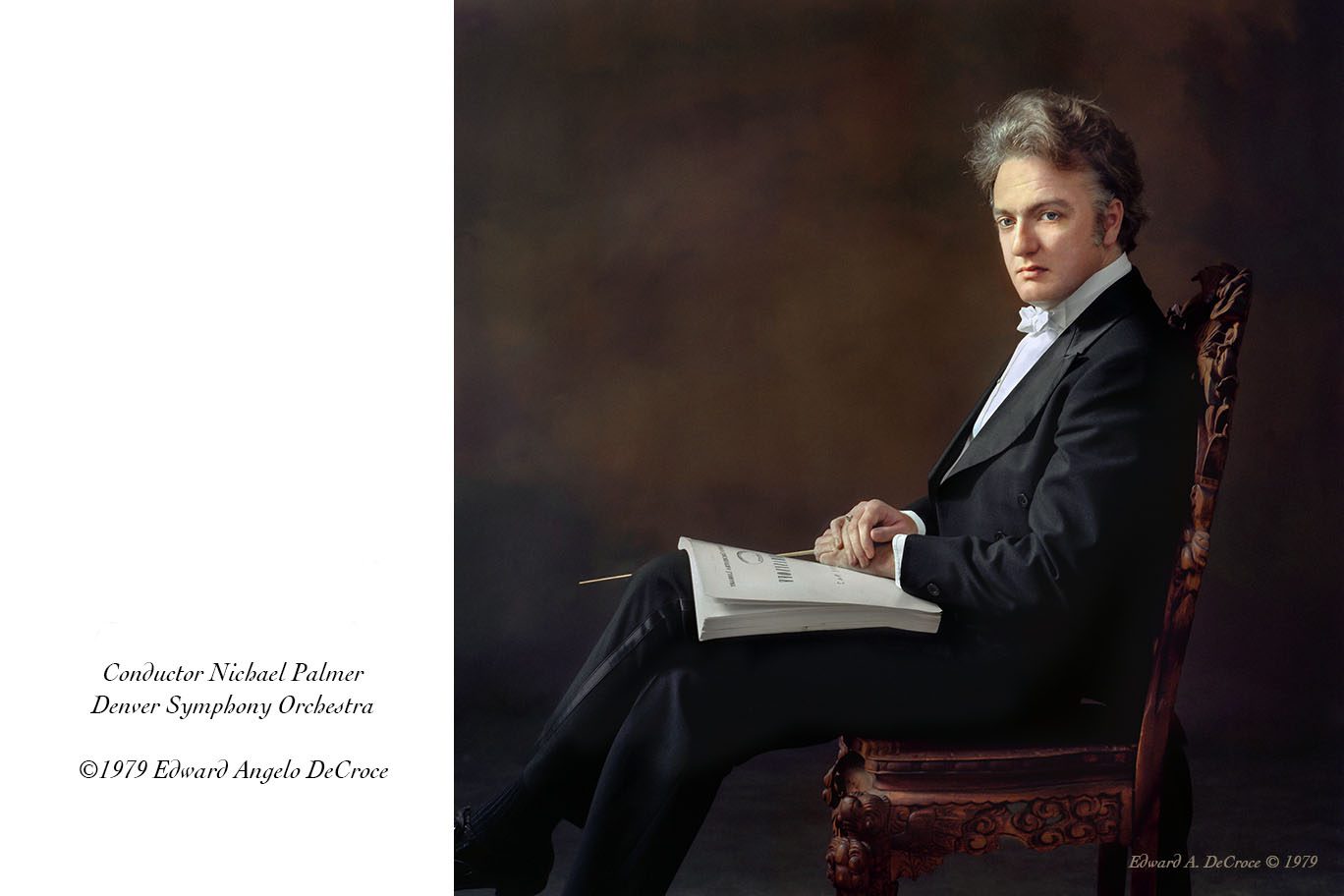

Gaetano Delogu was musical director of the DSO in 1979 when Denver portrait photographer Eward Angelo deCroce made this studio portrait. Delogu went on to conduct the Prague symphony until 1998.

.

The list of merits and accomplishments of Edward Angelo DeCroce is outstanding. He taught photography seminars and gave photography lectures in the USA, Canada, England, Australia and Denmark. He headed courses in contemporary photography at the West Coast School of Photography at The Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara Ca., and was on the faculty as a photography professor at The Colorado Institute of Art when he died in 1983.

Four of Mr. DeCroce’s works were selected for exhibition in the International Photography Hall of Fame when it was located in Santa Barbra Ca. He was awarded a Master of Photography PPA degree in 1966 and a Photographic Craftsman degree in 1970. He received the coveted American Society of Photographers (ASP) Fellowship Award in June 1978. In the 1960s he served as president for Professional Photographers of America (PPA) regionally. And he later served as national judge for the Loan Collection and PPA judging panels. Edward Angelo deCroce won the Kodak Academy Awards and had works included in the opening ceremonies at the Epcot Center in 1982.

From the 1960s until 1983, DeCroce’s works and his philosophy were published in photography magazines including Rangefinder, Studio Light, and The Professional Photographer. In 1972, Hasselblad Magazine published the first of three articles on the life and photographic works of Edward Angelo deCroce.

In “The Tide Changes” (Hasselblad 1972), DeCroce wrote: [For me] “There is no area of endeavor which is more personal nor more intimate than the photography of the human entity. No area of photography is more stimulating, challenging, demanding and rewarding than the photography of people.”

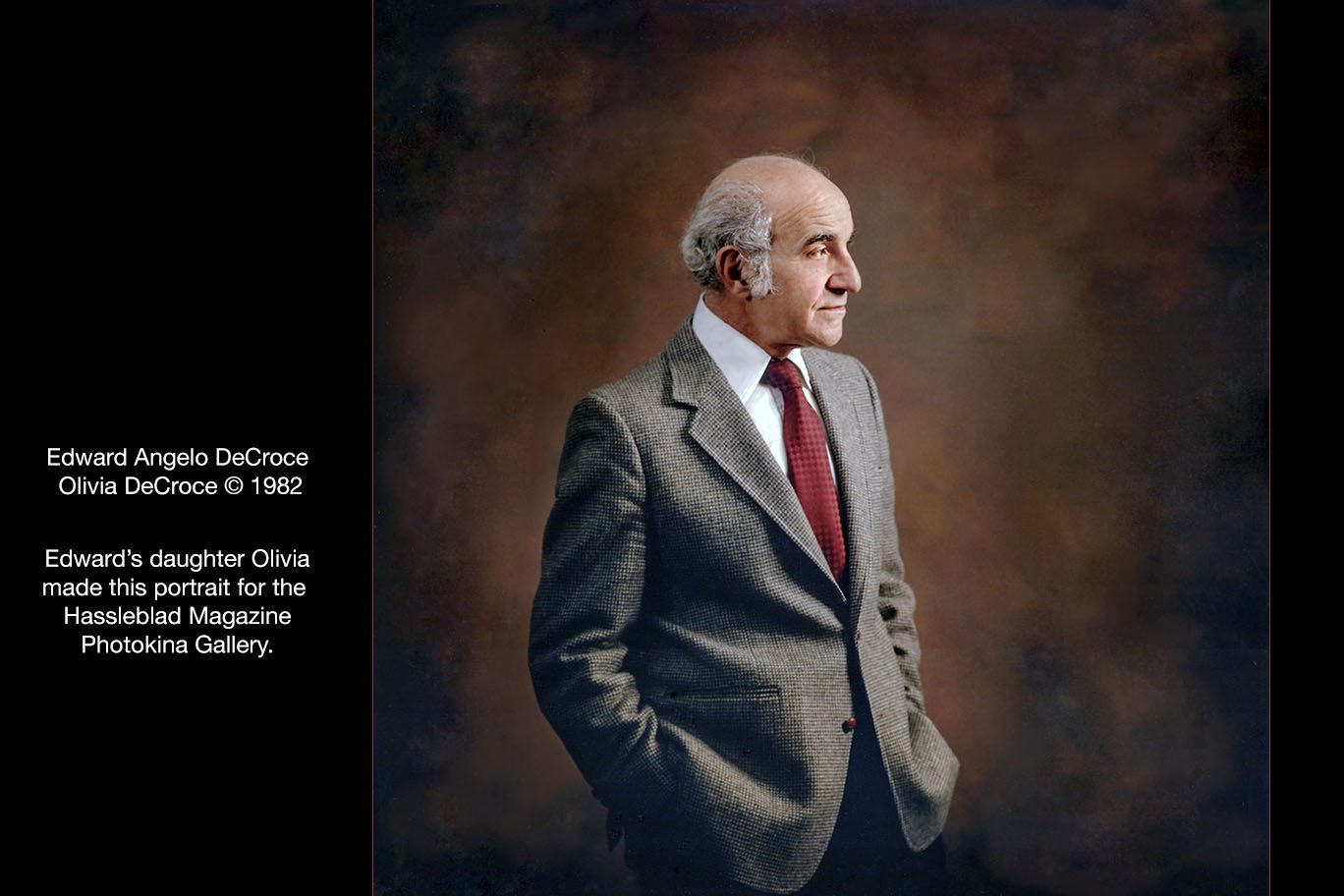

The Symphony Series by Edward A. DeCroce was debuted in its entirety by Hasselblad Magazine in 1978. And in 1982, deCroce was selected by Hasselblad Gallery as one of the top 10 photographers worldwide to represent the exquisite camera maker at Photokina 1982. Other notable photographers selected by Hasselblad that year were Americans Ansel Adams and photojournalist Judy Olausen along with science photographer Lennart Nilsson who first photographed an embryo in the womb.

The exhibit which included 10 works by each photographer traveled to museums and galleries internationally. It was just after DeCroce’s passing when the exhibit in the fall of 1983 arrived in Denver.

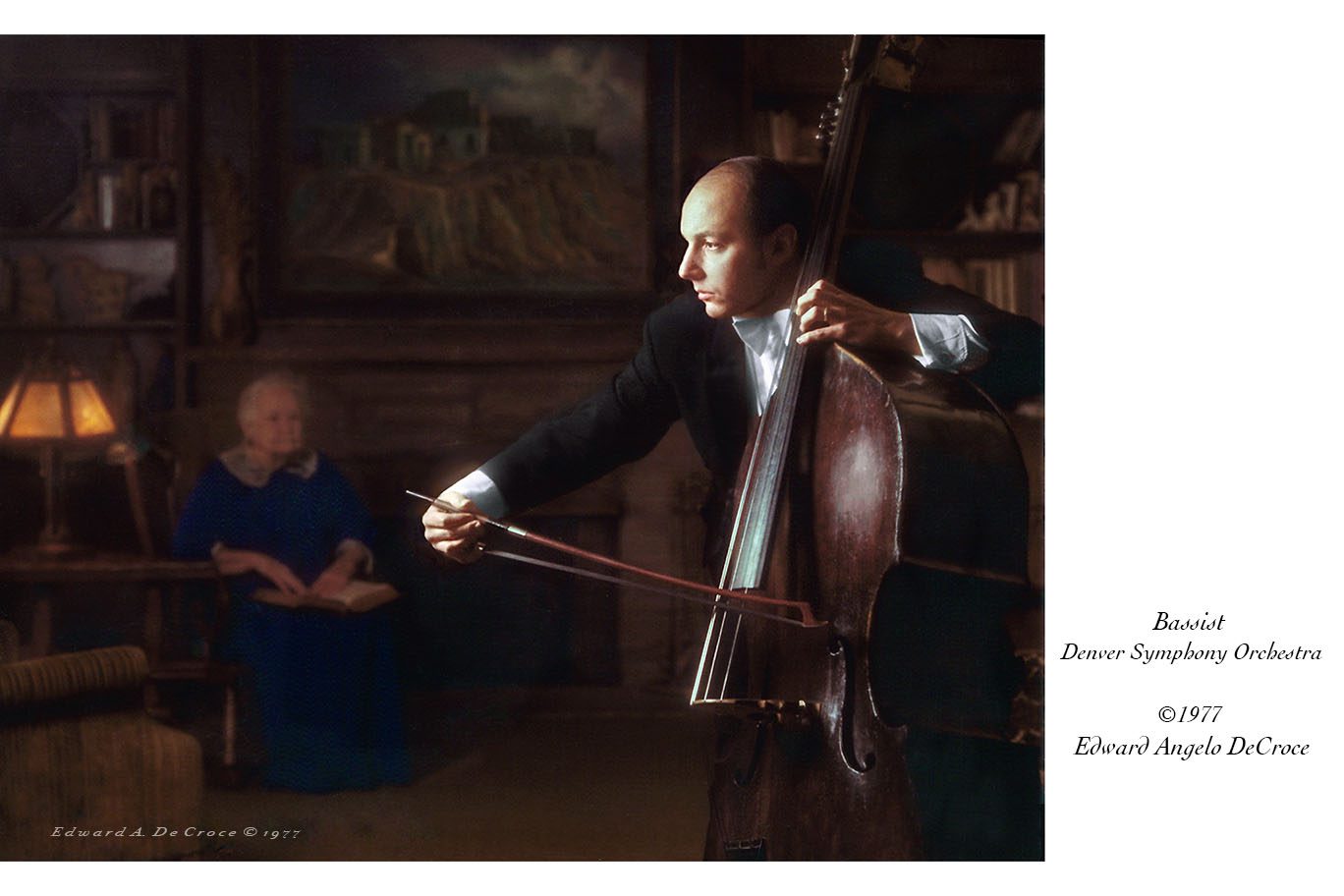

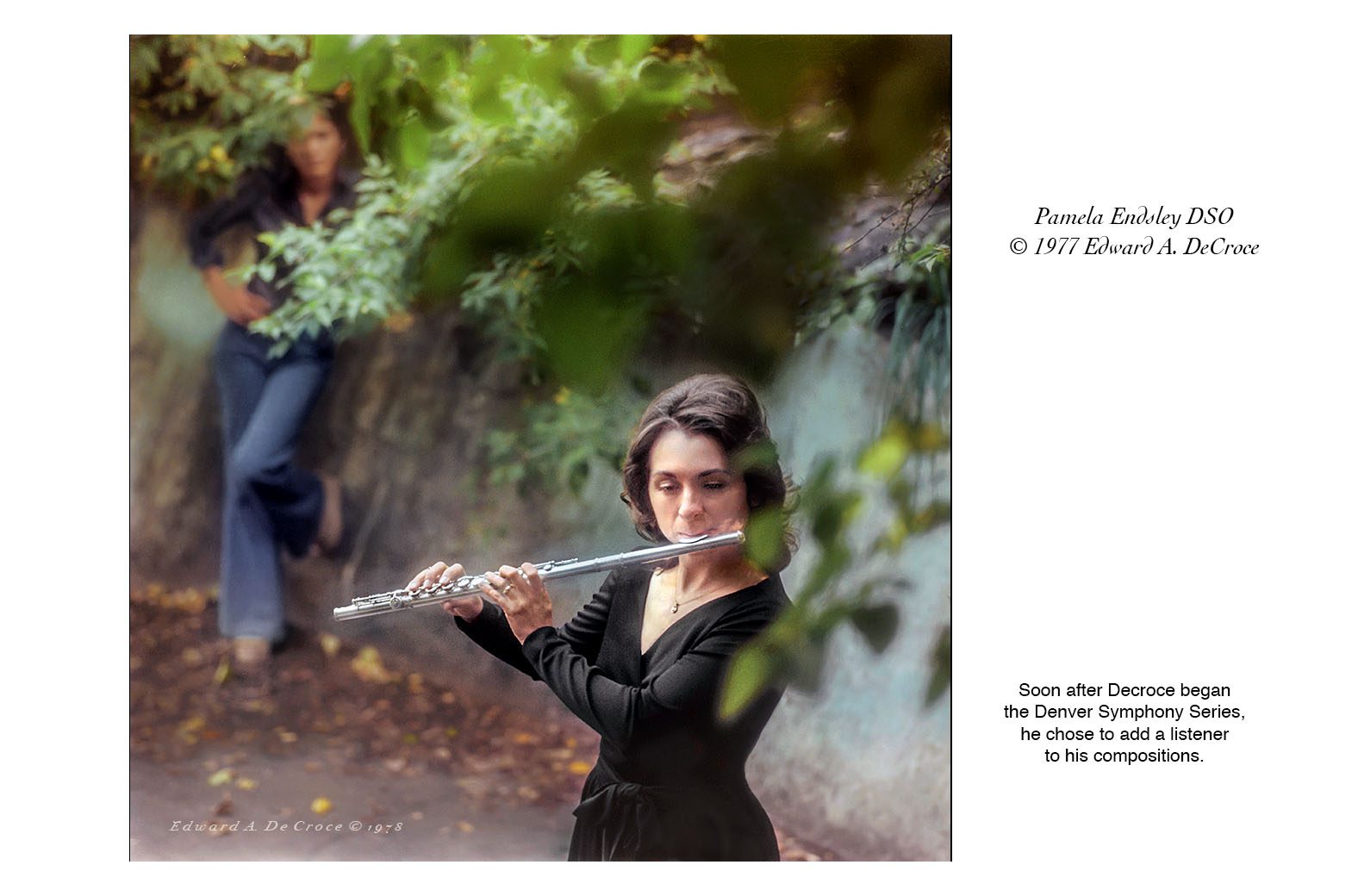

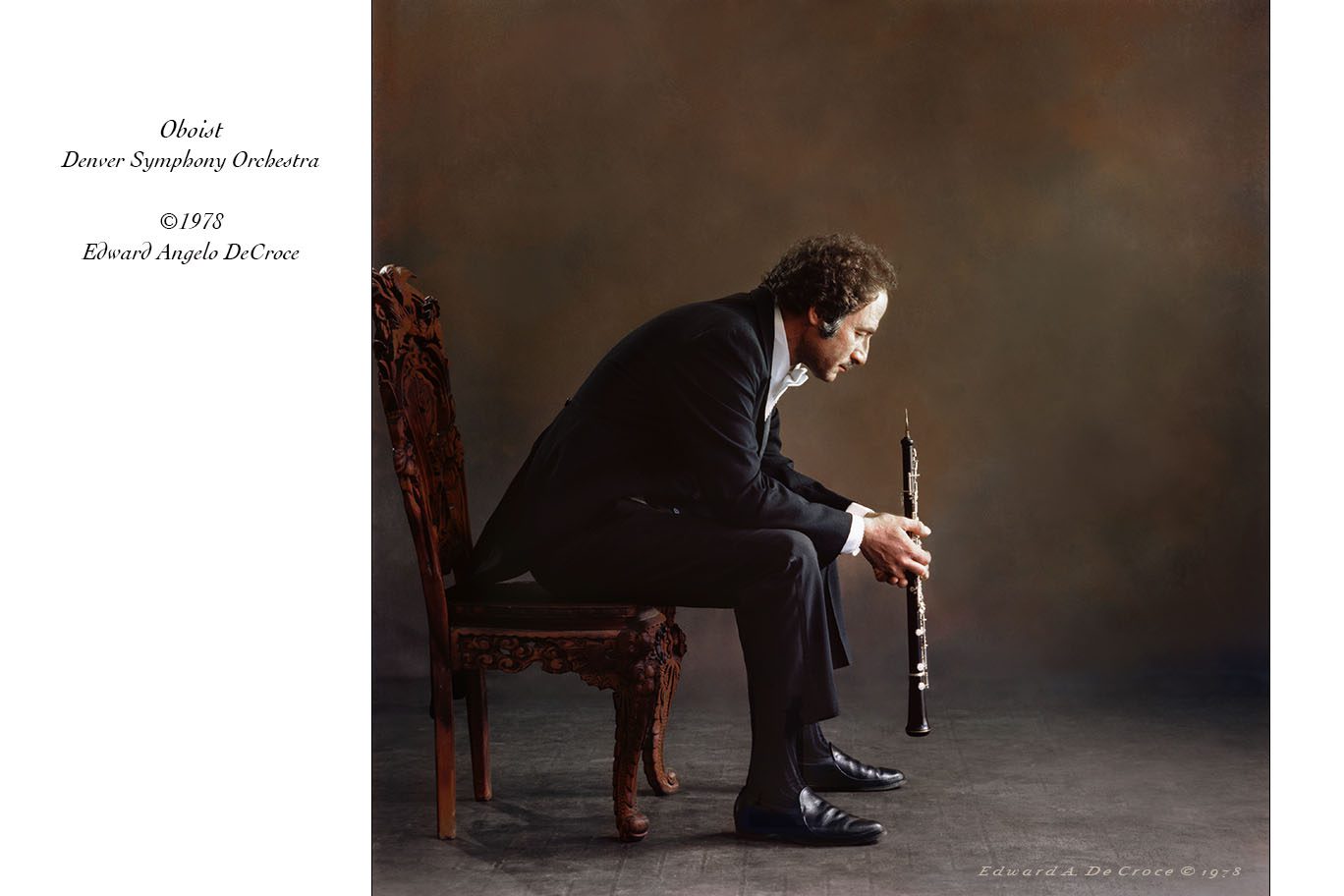

Denver portrait photographer DeCroce embarked in 1977 on a “self assignment” –– a photographic essay in portraits of the Denver Symphony Orchestra. With no commission from the DSO, DeCroce was free to explore. DeCroce wrote in “The Professional Photographer” (October 1979) “I was not compelled to please symphony management nor any individual musician. The challenge that faced me was how to imaginatively create a composition of each musician that was strikingly different than anything I had seen before.” Portrait works of the Denver Symphony were made into very large prints by Carol Small at the DeCroce lab, framed elegantly by Signe G. DeCroce and bequeathed to the DSO where they hung for decades in Boettcher Hall . The symphony series by DeCroce helped to garner world-wide recognition for the Denver Orchestra.

Hasselblad writer Evald Karlsten in September 1982 likened deCroce’s photographic portraits to Rembrandt. Karlsten wrote: “The thing that turned my thoughts to a past which is so remote and yet so near was seeing a series of color photographs taken by distinguished American photographer Edward Angelo deCroce. There is a Rembrandt touch about them, pictures depicting musicians in their work environments.”

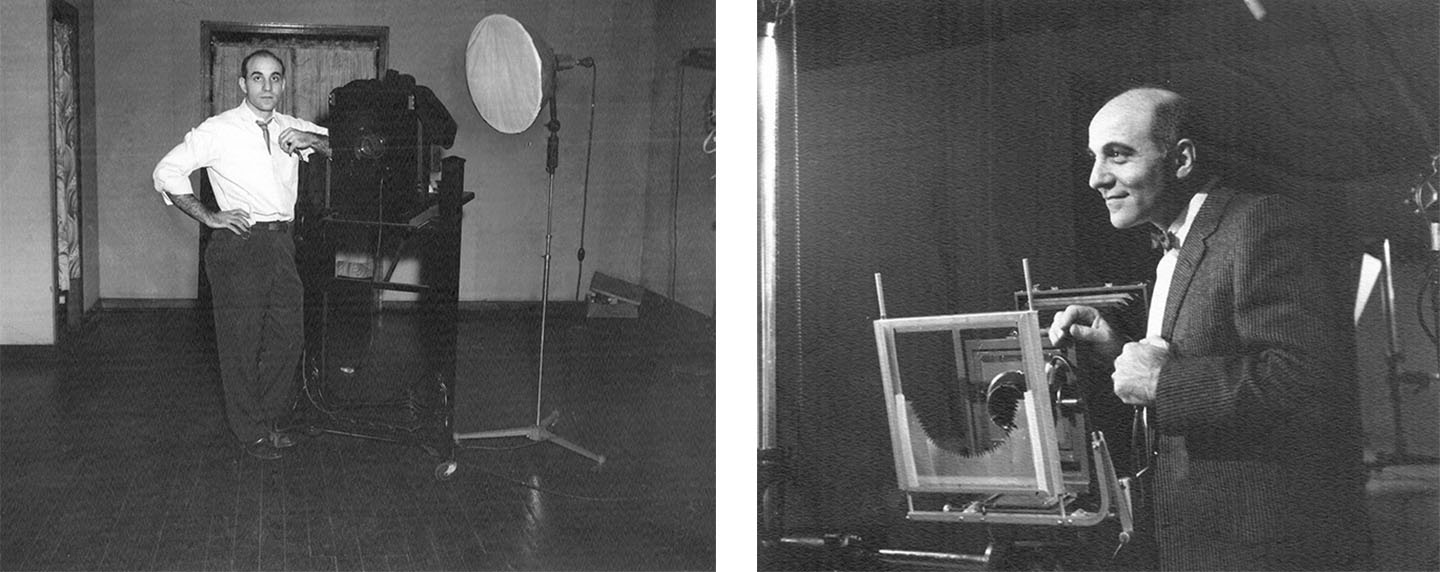

Forty years earlier in 1942, Edward’s first taste of photography came during WWII. Trained as an aerial photographer in the south Pacific, his job was to create both oblique and mosaic images for mapmaking. After the war, he opened his first portrait studio in his home town near Pittsburgh Pa before moving his family to Denver Colorado in 1957. Before opening his Denver studio in 1960, he worked for Kurt Jafay in the historic D&F Tower –– now referred to as the clock tower.

Denver portrait photographer Edward Angelo DeCroce embarked on a monumental photographic series when he began the Symphony Series in 1977. “Bassist ” ©1977 was composed in the photographer’s home. A neighbor lady posed as the listener.

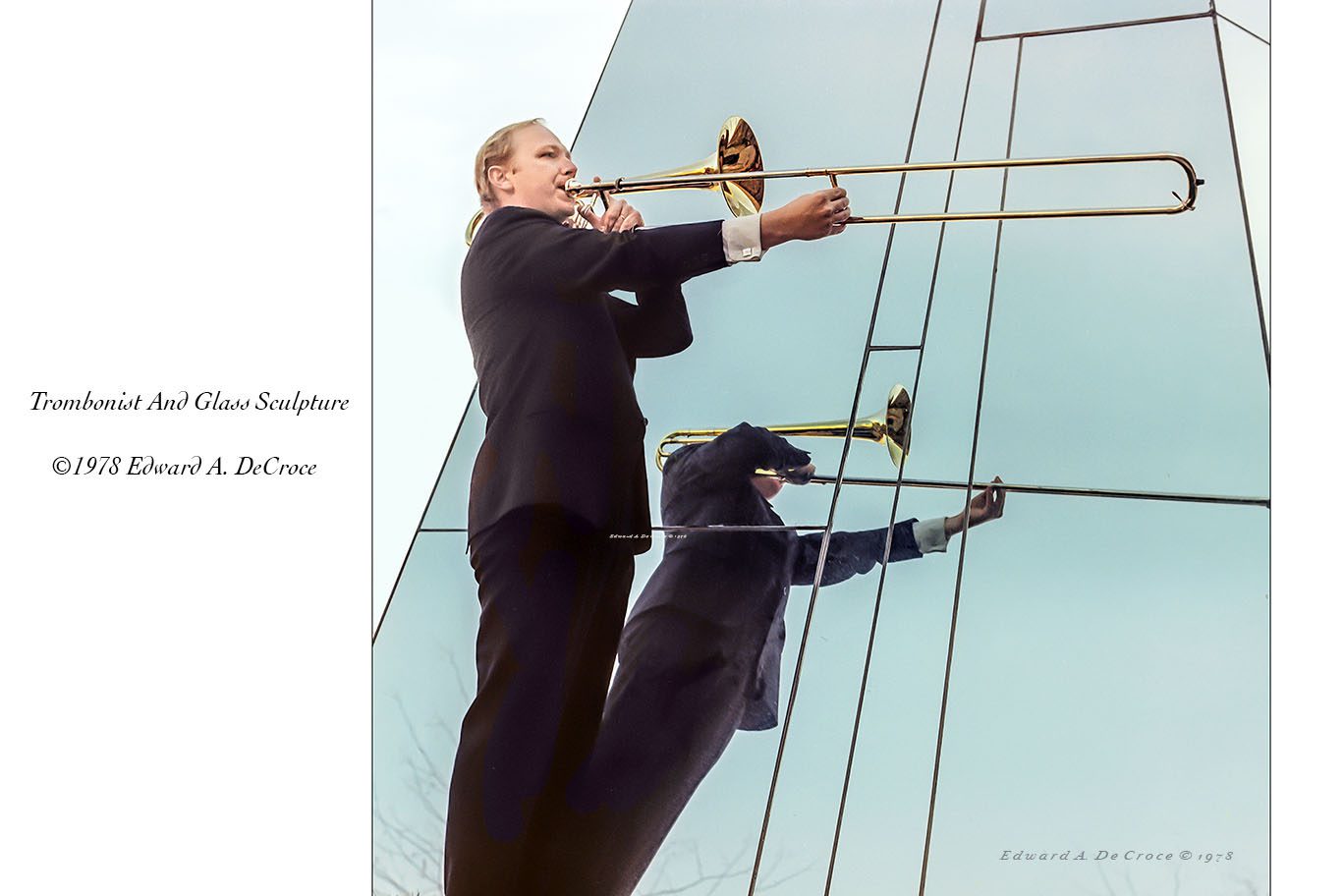

As the Denver portrait photographer progressed in the photo-essay of the Denver Symphony Orchestra, he began to include other art forms in his images like sculpture, dance, and painting

Soon after the Denver photographer began the Denver Symphony Series, he chose to add a listener to his compositions

As a young man in the mid 1930s and with his six siblings and mother.